Bini, people in southern Nigeria, are the largest Edo-speaking ethnic group. According to Joseph Greenberg’s classification, the Edo language belongs to the Benue-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo language family. Meanwhile, Kay Williamson and Roger Blench classify it as part of the Edoid subgroup within the Volta-Niger subfamily of the same language family.

Alongside the Bini, other Edoid-speaking groups include the Ishan, Urhobo, Isoko, and others. During the colonial period, the Bini dialect was recognized as the primary one. Based on it, a written script (using Latin characters) was created in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, laying the foundation for the modern Edo literary language.

The global Bini population is approximately 3.8 million, with the vast majority residing in Nigeria, particularly in Edo State. In the post-colonial period, a significant Edo-speaking diaspora has formed in Europe, North America, and Australia. In 2002, the diaspora established a global organization called the Edo Global Organization.

About 80% of the Bini people are Christians (Protestants and Catholics), while most of the remainder are adherents of a local syncretic Afro-Christian church called Arousa, headed by the traditional supreme ruler (Oba), and followers of indigenous beliefs. The latter are centered on ancestor worship, including veneration of the Oba, as well as cults of sacred animals, natural forces, and belief in the efficacy of magical rituals.

The Bini polytheistic pantheon is diverse, featuring deities that originated within the Bini culture alongside those rooted in the mythology of the neighboring Yoruba people, with whom the Bini are ethnogenetically and historically connected.

The supreme deity is Osa (or Osanobua), the creator of the world, but the most venerated deity is Olokun, associated with fertility, wealth, and water. The Oba historically combined the roles of supreme ruler and chief priest of the nation, though the professional priesthood has always been small and held a marginal role in society.

According to one ethnogenetic legend, the Bini’s ancestors came from the Middle East, while another claims they are indigenous to their current region. Scientific evidence, however, suggests that their ancestors migrated to their present location from the savanna belt, likely from the Niger-Benue confluence area (modern-day central Nigeria). After approximately three millennia in the savanna, they began to penetrate the forest zone around the 3rd–2nd millennium BCE, eventually settling there by the 1st millennium BCE.

The Bini were the founders of the “Kingdom of Benin,” which emerged around the city of the same name at the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennia CE. It became the most powerful political entity in the region during the mid-15th to the first half of the 17th century and retained its independence until the British conquest in 1897.

Testaments to the Bini’s high artistic culture of that era—the court art of Benin—now adorn collections in the world’s leading ethnographic and art museums. During the pre-colonial period, a now entirely forgotten system of information transmission through pictorial signs (phrases) existed, known only to a small circle of courtiers and priests.

The traditional occupation of the Bini is manual slash-and-burn agriculture, producing various types of yams, oil and coconut palms, maize, bananas, and vegetables. The main cash crops are cocoa, rubber, palm oil, and timber. Animal husbandry is underdeveloped, with sheep, goats, and poultry being the primary livestock. Cattle are kept only by wealthy individuals, primarily members of the traditional elite.

Fishing has never been of significant importance. Hunting retains a supplementary and ritual role. By the early colonial era, crafts had not yet separated from agriculture. Traditional crafts included weaving, pottery, wood and metalworking, and basketry, although these were partially supplanted by industrial goods in the late 20th–21st centuries.

Among the artistic crafts, bronze casting using the lost-wax method (the so-called Benin bronzes), ivory and wood carving stand out. Craftspersons remain organized into guilds, usually corresponding to traditional social divisions.

Historically, there has been a division of labor by age and gender. Internal and external trade was well developed even in the Middle Ages. The basis of social organization, both in villages and traditional Bini towns, is the extended family. Communities are typically unions of large families. Even in the 21st century, members of modern social strata often maintain traditional ties.

From the mid-1st millennium CE, communities were organized into larger units, often chiefdoms, which were later incorporated into the “Kingdom of Benin,” the highest hierarchical level of socio-political organization. Kinship is patrilineal, marriage is polygynous, strictly patrilocal, and exogamous.

The age-grade system and the secret male society Okerison are preserved. In the Kingdom of Benin, domestic slavery of war captives and criminals existed, and from the late 15th century, the Bini began selling slaves to Europeans. By the later pre-colonial period, a system of debt bondage had also emerged.

Traditional settlements, either linear (street-oriented) or circular, are usually located along roads. Houses are single-story, rectangular structures with wattle-and-daub walls on wooden frames or posts. The walls are plastered with clay inside and out. The roof is wooden, extending over the courtyard to form a veranda, and is covered with palm leaves, shingles, or thatch.

Today, urban residents and wealthy villagers build stone houses with gabled or hipped roofs made of corrugated iron. Single-room dwellings are being replaced by multi-room houses. On the plot allocated to an extended family household, residential buildings (corresponding to the number of its independent adult members) and utility structures are located.

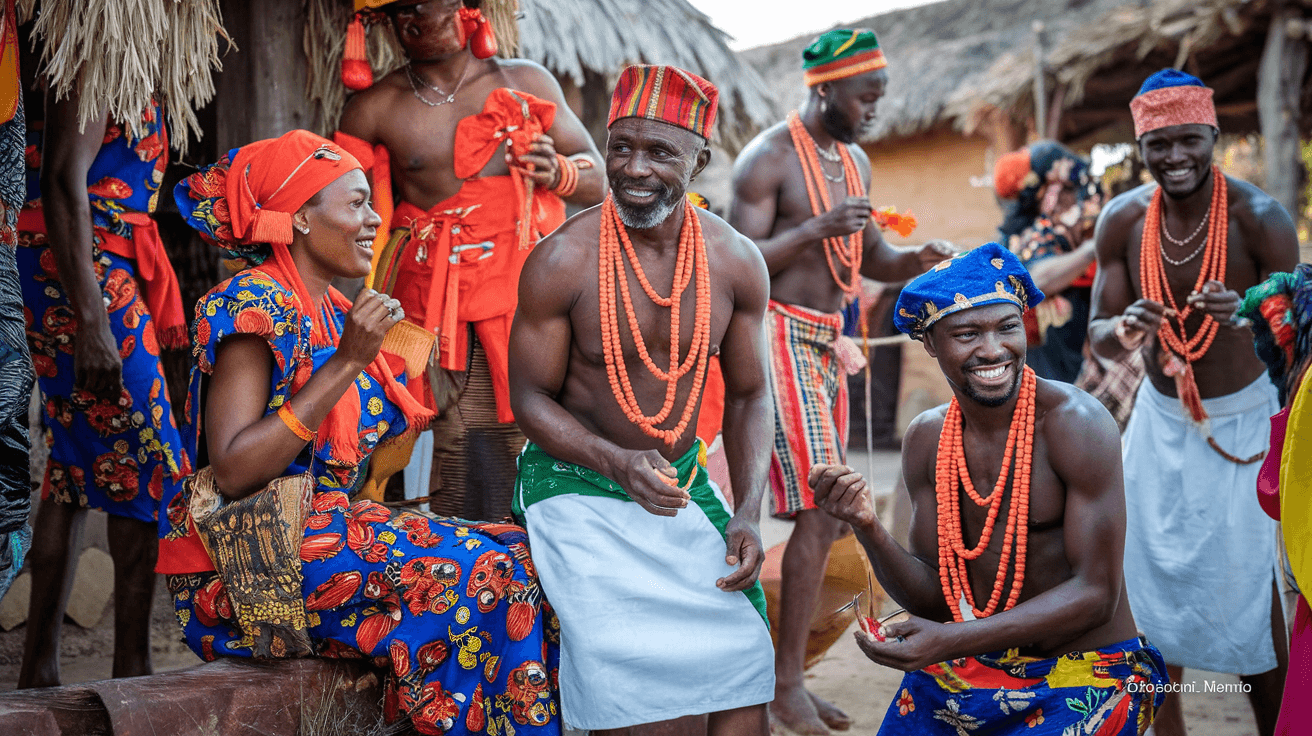

In addition to traditional waist or shoulder-wrapped clothing, modern Bini wear European-style attire and widely popular loose embroidered garments common throughout West Africa.

Traditional festivals, associated with agricultural and life cycles, are celebrated with dances accompanied by music. The main musical instruments include drums (with 17 known varieties), horns, bells, castanets, and a seven-string harp.

Rituals for the most significant celebrations, closely tied to indigenous beliefs and the political culture of the Bini, are still conducted by the Oba. Folklore is rich with historical legends, animal tales, and more.

Mythology is well-developed, featuring cosmogonic myths, stories of the origins of humanity, Benin, and others. Storytellers of tales, legends, and myths, present in every village, are highly respected.