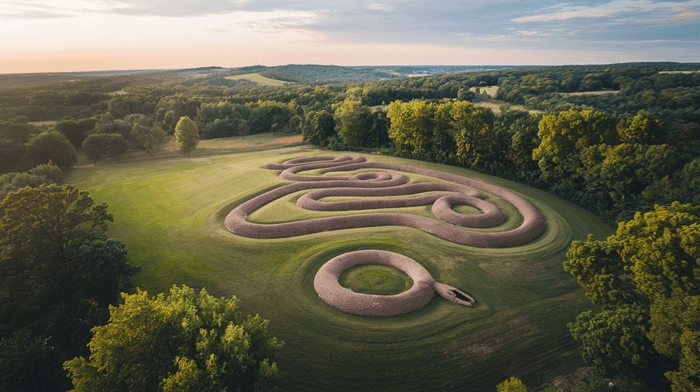

The Serpent Mound

Serpent Mound, deep in the Ohio Valley countryside, is the largest effigy of a snake in America — in fact, the whole world. This prehistoric earthen mound is about 1,375 feet in length, one and up to three feet high. The mound is about 20 to 25 feet across.

From above, the mound appears as a crescent-shaped snake of serpentine coils unraveling, with seven sinuous rings wedging its head from its tail. East are where the butt and the tail of the snake lies.

The tail of the snake ends in a triple ring, and the oval shape of its head gives the impression that the snake is trying to swallow an egg-shaped object roughly 121 feet long. Scientists are divided on whether or not this configuration of the geoglyph is fact or fiction. Some see in its oval enlarged eye the snake, other — a hollow egg, and still others — a frog that is about to swallow the widely-open jaws of the snake. And some scientists say they interpret the shape of the head as a lizard instead of a snake.

The mound follows the natural contour of the surrounding land, a high plateau that overlooks the Ohio Brush Creek. The head of the snake in fact curves towards the steep natural cliff above the creek. Such unique geological formations suggest that around 250-300 million years ago a meteorite fell on the site causing the folded bedrock under the mound, and still later a snake-shaped geoglyph was built, which was assembled from rocks strengthened with layers of yellowish clay and ash and filled with earth on top.

What we know about the Serpent Mound origin

The origin of the Serpent Mound has been debated by archaeologists for many decades. Excavation has produced no artefacts or burial that can directly identify when and for what it was erected.

At this time, there are two predominant theories. The mound may be of the Aden culture, from around 800 to 100 BC, some said. Others believe the mounds were most likely constructed by Native American groups that occupied the river valleys of the Mississippi, Ohio, Illinois and Missouri thousands of years ago, and which flourished within their fertile valleys.

Here the settled peoples cultivated corn, beans and pumpkins but left no written records. As local ranching developed and farming spread, many were destroyed in later times.

There is a theory that incorporates the above two and posits that they both might be right. The Aden culture may have had a hand in its construction — followed thousands of years later by ancient farmers who possibly repaired parts of it — the basic outline of which has endured until today.

What the Serpent Mound was created for

The competing theories of when, or for that matter why, Snake Mound was created, separated by millennia, suggest that there is still much to learn both about the geoglyph and also what ancient humans designed it for.

There are still many North and Central American indigenous mortuary practices that had supernatural powers ascribed to snakes or reptiles as part of their spirituality. Indigenous peoples of the Middle Ohio Valley, in particular, frequently made snake forms from sheets of copper. So, perhaps it was a ceremonial mound.

Because the summer solstice sets where the serpent’s head aligns, and the winter solstice rises under the tail, the theory is that the mound may have been used to keep track of time or the shift of the seasons, possibly indicating when to plant or harvest.

Further, the curves of the snake’s body have been recognized as parallel to the lunar phases or, vice versa, at least coinciding with the two solstices and two equinoxes, but since they are so diffuse in the contemporary terrain, a true appreciation of their meaning may forever campaignd unproved.

If you draw the quintessential shape of the snake throughout the Ohio Valley, it will resemble the Dragon constellation, and Polaris (the North Star) fits within the placement of the initial curvature of the snake torso from the head. The alignment of the mound with Polaris could mean that it was used in finding true north, and, in a sense, was a compass.